Science of Thanksgiving: From Food Safety to Golden Perfection

With Thanksgiving approaching and laboratories across the country making plans for the holiday break, it's worth taking a moment to appreciate the remarkable science behind the centerpiece that graces millions of tables – turkey.

Whether you spend your days running PCR assays or managing procurement for research facilities, that bird on your holiday table also represents a fascinating intersection of food safety protocols, biochemistry and culinary science that would make any lab professional appreciate the complexity hidden beneath that golden-brown skin.

Your Lab Skills Come Home for the Holidays

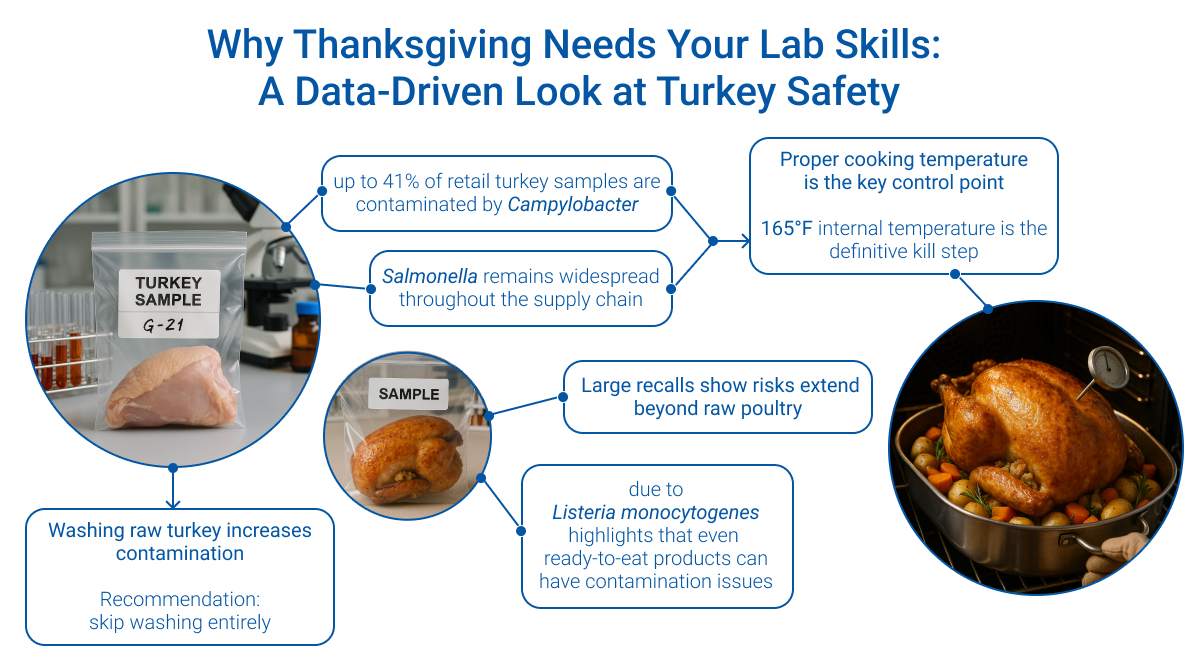

For those of us who understand contamination protocols and pathogen detection, the term “turkey safety” takes on a new kind of significance. Recent data shows why laboratory vigilance matters: Campylobacter used to contaminate up to 41% of retail turkey[1] samples, while Salmonella affects a significant portion of the supply chain[2] as evident by the 2018-2019 Salmonella Reading outbreak[3] that infected 358 people across 42 states. It marked the first time federal agencies engaged an entire industry rather than targeting a single facility, finding systemic contamination that would have any food safety lab working overtime with their XLD agar plates and selective enrichment broths.

The critical control point remains unchanged: 165°F internal temperature, measured with the same precision you'd apply to any thermal cycling protocol. You can think of it as your holiday qPCR: three measurement sites (breast, thigh and wing), proper calibration and no shortcuts with those pop-up timers that are about as reliable as expired reagents.

The October 2024 BrucePac recall of 12 million pounds of meat[4] due to Listeria monocytogenes contamination reminds us that even ready-to-eat products require the same sterile handling you're used to seeing in cleanest BSL facilities.

Here's a protocol many food safety labs now recommend: skip the traditional turkey washing step entirely[5]. Studies demonstrate that washing spreads pathogens through aerosol dispersion, essentially creating the same contamination risk you work so hard to prevent in your lab environments with HEPA filtration, laminar flow hoods and filtered pipette tips. Instead, treat raw turkey like you would any biological sample[6]: dedicated work surfaces, proper containment and immediate decontamination of all contact surfaces with the same rigor you'd apply when working with Petri dishes and inoculation loops.

The Plant-Based Alternative of Protein Engineering

For laboratory professionals interested in food technology, plant-based alternatives like Tofurkey[7] can be viewed as an exciting protein engineering challenge. The iconic “Tofurkey roast” relies on vital wheat gluten (seitan) and organic tofu to create meat-like texture through careful manipulation of protein structures.

The science around it involves exploiting gluten's unique viscoelastic properties and tofu's thermal coagulation characteristics. Field Roast takes a different approach with their “grain meat” technology, incorporating complex carbohydrate matrices from butternut squash and lentils. Quorn pushes the boundaries further with mycoprotein derived from Fusarium venenatum controlled fungal fermentation producing naturally fibrous protein structures that would intrigue anyone working with microbiology (and culturing on Sabouraud dextrose agar or monitoring growth with automated incubation systems).

The nutritional profile presents interesting trade-offs: complete elimination of cholesterol and significant reduction in saturated fats, but sodium levels 5-10 times higher than conventional turkey. It's a formulation challenge that mirrors many pharmaceutical development projects that optimizing one parameter while managing others, much like balancing selective media compositions or fine-tuning HPLC gradients for optimal separation.

Chemistry Behind the Golden Glow

Transforming your turkey's surface is the Maillard reaction[8] that represents one of the most complex chemical cascades in food science. First described by Louis-Camille Maillard in 1912, this non-enzymatic browning begins around 284°F and generates hundreds of volatile compounds through a multi-stage process that would make any organic chemist appreciate its elegance.

The reaction initiates when carbonyl groups from reducing sugars react with nucleophilic amino groups from amino acids, forming glycosylamines that rearrange into ketosamines. Through dehydration, fragmentation, and Strecker degradation, these intermediates produce the signature compounds[9]: pyrazines for nutty notes, furans for caramel flavors and thiophenes for that distinctive roasted character. The key "meaty" molecules – 2-methyl-3-furanthiol and bis(2-methyl-3-furyl)disulfide – both contain sulfur derived from cysteine interactions.

The critical factor? Surface moisture must be eliminated first, since water prevents temperatures from exceeding 212°F. It's basic thermodynamics that explains why air-drying your turkey overnight in the refrigerator produces superior results, creating the optimal reaction conditions for maximum compound generation.

Protein Denaturation or The Physics of Perfect Doneness

Understanding protein behavior under thermal stress explains why turkey breast becomes desert-dry when overcooked while thighs benefit from higher temperatures. The two primary muscle proteins exhibit distinct denaturation profiles that any protein biochemist would recognize.

Myosin denatures at 104-122°F, creating desirable firmness, while actin denaturation begins around 151-163°F and triggers myofibrillar contraction, essentially wringing moisture from the muscle fibers like a molecular sponge[10]. Moisture loss accelerates dramatically above 150°F, creating the classic overcooked texture.

The conundrum involves collagen conversion: transforming this connective tissue protein into gelatin requires prolonged heating above 160°F, but this temperature range drives moisture loss in lean breast meat. Dark meat's higher collagen content explains why thighs benefit from cooking to 165-175°F while breast meat[11] reaches optimal texture at 150-160°F - differences that could be quantified using hydroxyproline assays or protein gel electrophoresis to track collagen degradation.

Resting allows contracted proteins to partially relax while redistributing moisture through the tissue – like protein refolding and equilibration, processes familiar to anyone who's worked with enzyme preparations.

The Science of Gratitude

As we move away from laboratory benches to family tables this Thanksgiving, it's remarkable to note how the same scientific principles that guide our daily work – contamination control, protein chemistry, thermal dynamics – apply to creating a perfect holiday meal. Whether you're pipetting samples or carving turkey, precision, understanding of underlying mechanisms and following proper protocol remains essential.

From all of us who appreciate the beautiful complexity hiding in everyday experiences, have a wonderful Thanksgiving filled with perfectly cooked turkey, great science conversations and the joy of discovery even at the dinner table.

You might be also interested in:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

When is turkey safe to eat?

It is safe to eat when cooked properly. Cook turkey to 165°F internal temperature to kill harmful bacteria like Salmonella and Campylobacter. Use a food thermometer to check the thickest parts of the breast and thigh.

Why does roasted turkey turn brown?

The brown color comes from the Maillard reaction, a chemical process that happens when proteins and sugars are heated together. This reaction also creates the savory flavors we associate with roasted meat.

Why does turkey breast get dry when overcooked?

Turkey breast has proteins that squeeze out moisture when heated too much. The proteins contract and push water out of the meat, making it dry. Dark meat has more connective tissue that helps it stay moist.

How does brining really make turkey juicier?

Brining works by changing the protein structure in the meat so it can hold more water. Salt breaks down some proteins and helps the turkey retain moisture during cooking.

Should you wash raw turkey before cooking?

Washing can spread bacteria around your kitchen through water splashing. Just pat the turkey dry with paper towels and cook it to the proper temperature.

How do you prevent cross-contamination when handling turkey?

Use separate cutting boards for raw turkey and other foods. Wash your hands with soap for 20 seconds after touching raw turkey. Clean all surfaces and utensils with hot soapy water or disinfectant.

List of References:

- ScienceDirect - Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in Retail Chicken, Turkey, Pork, and Beef Meat in Poland between 2009 and 2013

- National Library for Biotechnology Information - Prevalence of Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella Serovars in Retail Chicken, Turkey, Pork, and Beef from the Greater Washington, D.C., Area

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Infections Linked to Raw Turkey

- ABC News - Listeria recall expands to nearly 12 million pounds of meat

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - Preparing Your Holiday Turkey Safely

- Food Safety and Inspection Service - Turkey Basics: Safe Cooking

- The Spruce Eats - What Is Tofurky?

- Serious Eats - An Introduction to the Maillard Reaction: The Science of Browning, Aroma, and Flavor

- Donald S. Mottram - Flavor Compounds Formed during the Maillard Reaction

- ThermoWorks - How Heat Affects Muscle Fibers in Meat

- BBQ Champs Academy - The Science Behind Resting Meat